Science and TEK

Colonization brought many changes to the north American continent. Not the least of which is how the human environment is managed. Extractive economies- mining, logging and damming rivers for ‘cheap’ energy became the governing business model for generations and still is. The notion that we would eventually ‘run out’ was foreign in this land of plenty…this Eden.

Ecological knowledge was common and widely used by native cultures long before colonization by European settlers. Only recently has the term “Traditional Ecological Knowledge” become fashionable. European colonization introduced different values and perspectives to the native cultures. And often with negative consequences. A classic example has been fire exclusion in the forest. Over the course of generations since Euro settlement, fire exclusion has allowed fuels, stand and forest structure to alter dramatically. Shade tolerant, climax species have dominated many forest types for decades and resulted in historic levels of ground and ladder fuels. Catastrophic, stand replacing fires have become the norm in hardwood and conifer forest systems.

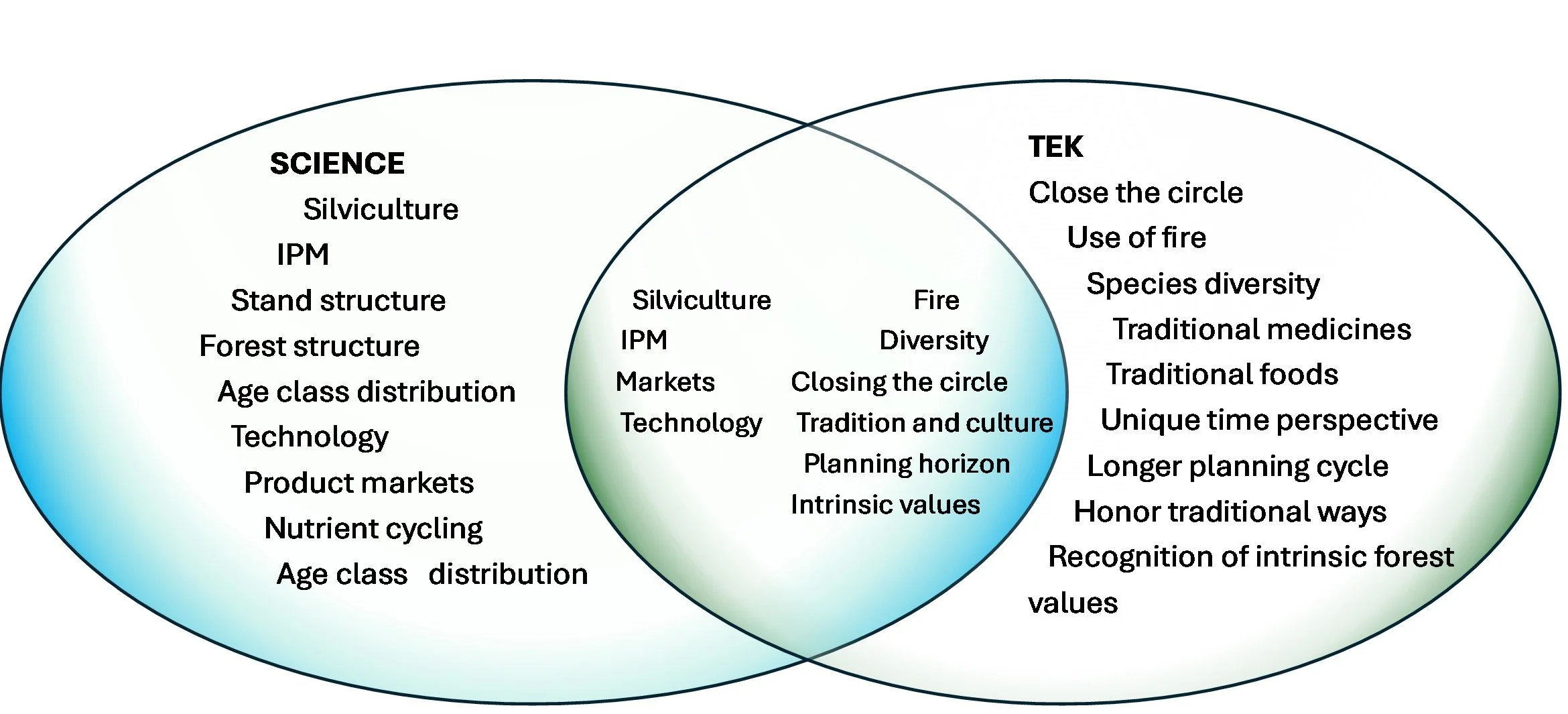

The following Venn Diagram exhibits many, but not all attributes of land management efforts of Euro-settlers and native cultures and where they could complement each other’s efforts to fashion sustainable economies and create a living environment.

Perhaps the greatest distinction is their differing perception of time. The Yurok Tribe reminds all that they have been in the Klamath Basin for 36,000 years. They have witnessed redwood forests burn, regenerate, mature, senesce, age to ‘old growth, collapse, and regenerate hundreds of times. Their ‘planning horizon’ is generations long. Whereas the white power structure is content with ‘keeping the wheels on’ three months at a time. The tragedy is not that the white culture condones the cutting of 300-year-old trees, or 800-year-old trees, or even 1,500-year-old trees as in the case of redwoods . No, the real tragedy is that the white culture is not willing to make the 300 or 800- or 1,500-year commitment to grow a tree like it.

Fire exclusion in the forest since Euro-settlement has created stand structures and forest structures favoring catastrophic wildfires. Natives understood the role of fire in the forest and actively promoted its use a management tool. With Euro-settlement, fire was banned by Federal agencies and indeed native practitioners were often jailed for implementing it. Fire was an important tool used to promote native species- species critical for foods and medicines. It ‘closed the circle’ by promoting diversity, returning nutrients to the soil, and its use maintained and honored traditional ways.

Managing the human environment was paramount to Indigenous cultures. After all, it provided their shelter, food and medicines. Their culture and tradition passed from generation to generation directed them to implement certain practices to maintain a sustainable existence. These practices became part of their ‘book of Traditional Ecological Knowledge’ (TEK). TEK was not understood by European settlers nor recognized and appreciated for the guidebook it provided for sustainable existence. Indeed, much useful information can still be derived from it to promote sustainable economies and a living environment.

Science can contribute an understanding of silviculture and the role it can play in stand structure, forest structure, and age class distribution- the three components critical to a sustainable forest. Silviculturists manage short- and long-term risks with prescriptive treatments. These treatments are critical to managing diseases and insect threats.

The following anecdotes provide a real-world example of the application of appropriate silviculture to manage forest structure and an integrated pest management application to control a common parasite in many forests.

The Yakama Nation has significant acres of valuable forest lands and forests on the east slopes of the Cascade Range in western Washington State. They have a variety of forest types ranging from the dry ponderosa pine forest fringe to the higher elevation white bark pine forest. In the early 2000’s, a spruce budworm irruption started defoliation in the true fir types on a large portion of the commercial forest base. Approximately 210,000 acres were in the grand fir/ true fir mosaic of habitat types. After three cutting cycles where the standard prescription was “thin from below” to a basal area target, a dense understory of shade tolerant true fir and Douglas-fir developed under this canopy of fir species. The result produced ideal habitat for the spruce budworm. Host species are typically Douglas-fir, all true firs, spruce, western larch, but may be found on pine species. Spruce and fir forests throughout North America are subjected to annual growth losses and tree mortality due to irruptions of the spruce budworm population.

Repeated thinning from below silviculture prescriptions resulted in extensive acres of grand fir and true fir habitat. This forest type allowed the development over time of widespread and consistent ideal habitat for the spruce budworm. This huge area of ideal habitat provided for an irruption- an extensive and long-term population growth of bud worm to develop. The larvae typically feed on new foliage, flowers and cones over several years and predispose the trees to bark beetles and even root diseases. However, creating openings with group selections and introducing a younger cohort of more tolerant early seral species with each harvest entry would have built structure into this forest type. Group selections or even gap-based silviculture would break the continuity of host material and discourage the spread of the budworm while still maintaining an uneven-aged silviculture system. In the final analysis, the culprit in this case was not the budworm, but the lack of appropriate silviculture.

Silviculturists manage risk with treatments. Any failure to apply the appropriate silviculture has a significant risk in and of itself.

Mistletoe is a parasitic fungus unique to virtually every tree species and their distribution and severity typically corresponds with their host’s range. They are flowering plants and as parasites, depend almost entirely on the sugar compounds produced by their hosts. Productivity loss, poorly formed trees, top kill, mortality, increased ladder fuels, and predisposition to bark beetle attack often result from dwarf mistletoe infestation.

The Spokane Tribe implemented uneven aged silviculture and managed regeneration with patch cuts and group selections in the dryer habitat types where mistletoe was an issue on their land base. These regeneration units were typically three to five acres (1.2 hectare to 2.0 hectares) in size. If mistletoe was present in the overstory in Hawksworth rating 1-3 and regeneration was not a goal and stocking was 80 basal area or more, then the overstory was maintained until the next cutting cycle. However, if the overstory had Hawksworth mistletoe ratings of 4-6, it was marked for harvest. It was not the intent of silviculture and management efforts to eliminate the disease. But rather isolate it in manageable patches. It does provide a food source for birds and animals and the brooms also provide a nest site and cover for birds and animals.

The Yakama Tribe implemented even aged management in their dryer forest types. They typically used a seed tree prescription in an effort to make it look like ‘not a clearcut”. However, they left trees with mistletoe in the 1, 2, and 3 Hawksworth ratings scales. The end result being a widespread infestation of mistletoe in the regeneration. The widespread infestation caused by the application of inadequate silviculture eliminated the potential of isolating mistletoe in patches and small groups. Failure to integrate silviculture as a pest management tool resulted in a forest structure that will have long term negative growth and yield consequences, increasing cull tree component and top kill, increasing mortality, and cumulative predisposition to bark beetle attack.

In both instances, appropriate silviculture would have led to different outcomes.

Silviculturists manage risk with treatments. Any failure to apply the appropriate silviculture has a significant risk in and of itself.

In the final analysis, silviculture rules!

Edward Mann Global Forest Resources LLC 12/27/2025